0

-

An empty cart

You have no item in your shopping cart

envato-wordpress-toolkit domain was triggered too early. This is usually an indicator for some code in the plugin or theme running too early. Translations should be loaded at the init action or later. Please see Debugging in WordPress for more information. (This message was added in version 6.7.0.) in /var/www/wp-includes/functions.php on line 6121g5plus-darna domain was triggered too early. This is usually an indicator for some code in the plugin or theme running too early. Translations should be loaded at the init action or later. Please see Debugging in WordPress for more information. (This message was added in version 6.7.0.) in /var/www/wp-includes/functions.php on line 6121The removal of suspended solids is usually achieved in three processes, an inlet screening, followed by two stages of sedimentation. The influent sewage carries with it a wide range of solid objects that are put into the sewage system or that fall into it, such as dead animals, rags, sticks, human waste, and so on. These objects may be floating or suspended in the flow, so the incoming flow must be put through a screen to remove the larger objects, to prevent their causing a blockage or damaging equipment further into the process.

These larger suspended or floating objects are removed in a full-flow screen, through which the whole sewage flow passes. This can be a vertical bar grate, which is scraped clear of trapped solids on a regular basis, or a moving screen that

transports the collected material out of the liquid flow.

The sewage then passes through a grit trap, in which the flow velocity is adjusted to allow the settlement of inorganic sand and grit particles (that are mostly swept along from roads and roofs by stormwater), but not the softer and less dense organic particles, which are carried through this trap. As most organic material does not settle with the grit, this can be scraped out of the trap, washed and sent to landfill.

With large objects and easily settled solids removed, the flow rate of the sewage can now be measured (perhaps by a notched weir) as a guide to how downstream processes should be set, but also as in indication of a storm-driven surge in liquid flow. Under the circumstances of a storm surge, most works will have storm tanks awaiting this eventuality. Some of the main flow is then diverted into temporary storage in the tanks, and released slowly back into the main flow once the storm is over.

These tanks will have to be designed recognizing that there will be suspended organics in the diverted water, and these must not be allowed to build up in the storm tanks.

The third primary process is a settlement stage, in which the sewage is held in large open tanks, with a gentle liquid motion in them, which will allow the settling out of the heavier organic solids. They are also designed with grease traps at their tops to remove floating fats, oils and grease. The organic content of the sewage is reduced by 25–50% in this sedimentation process, and a considerable amount of primary sludge is accumulated, which must be removed regularly, if not continuously.

The grit trap and primary settlement system are both sedimentation devices, the first with quite a high liquid flow, sufficient to allow the dense sand and grit to settle, but to retain the lighter organic material in suspension. The majority of the suspended organic matter is then removed in large settling tanks, in which the solids fall to a sloping floor and the clarified liquid flows out over a weir at the top of the tank and then under a grease trapping baffle. The solids on the bottom of the tank are raked to a central point (in a circular tank) or to one end (of a rectangular tank) and discharged as a thin slurry.

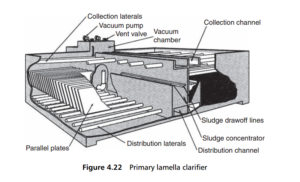

Such a clarifier takes up a large ground area, but a more complex design is available ( Figure 4.22 ) using a lamella separator system, with a much smaller footprint.